In 2001, two aircraft went head-to-head in a competition for the massive Joint Strike Fighter contract. The winner of the competition would go on to become the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II, while the loser, the Boeing X-32, would live on largely as a punchline for its unconventional looks. There’s much more to the story of the X-32 than meets the eye, though. In a recent interview, the chief test pilot for the X-32 program tells us all about the jet and why it lost to the X-35.

That pilot is now-retired Commander Phillip “Rowdy” Yates, a former Naval aviator who had served as, among other things, the F-14 Tomcat air-to-ground weapons test officer for Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 23 (VX-23) at Naval Air Station Patuxent River. In a YouTube interview published last year, Yates sat down with Ward “Mooch” Caroll, a retired Navy Commander who served as an F-14 Radar Intercept Officer and is the current Director of Outreach and Marketing for the U.S. Naval Institute, as well as a published author.

In the 1990s, the Department of Defense began conducting studies on the development of a family of aircraft to replace a wide range of existing fighter and strike aircraft. Several aerospace companies submitted designs for what was then known as the Joint Advanced Strike Technology program (JAST). At the request of Congress, the JAST program was joined together with an existing Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) program to develop a short-takeoff/vertical landing (STOVL) tactical jet with advanced capabilities. And thus, the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program was born.

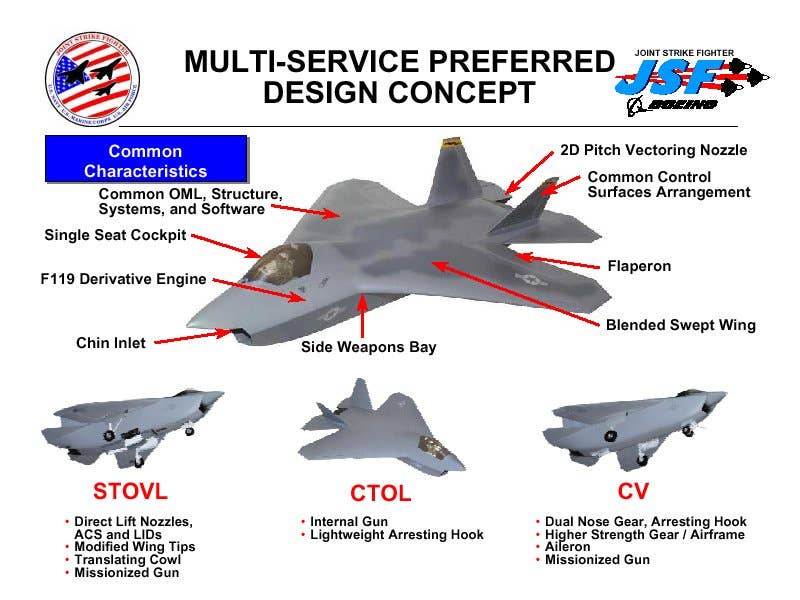

The JSF program eventually settled on entries from two companies, Boeing and Lockheed Martin, who would demonstrate their competing designs for the program’s concept demonstration phase. From 1997 to 2001, both of the firms were tasked with building and flight testing two aircraft that could demonstrate capabilities for three separate variants: conventional takeoff/landing, short-takeoff/vertical landing, and carrier takeoff/landing.

The Boeing X-32 and Lockheed Martin X-35 at Edwards Air Force Base., USAF

It was while serving with VX-23 that Yates got a call asking him if he’d like to be one of the first pilots to fly the X-32 or X-35 as part of the JSF competition. In a 2003 interview with the PBS series Nova, Yates said the chance to test the X-32 was the high point of his career as a test pilot. “Dream come true. You can use all those trite phrases. A lot of my peers and contemporaries were probably pretty jealous of what I was able to do with the X-32. I don’t know how to say it any better than just that it was the highlight of my career.”

Test Pilot Phillip “Rowdy” Yates sitting inside the X-32., PBS

Yates initially worked alongside a single team of test pilots and engineers supporting the development of both fighters. One year prior to the actual first flight tests, Yates was assigned to the X-32 program, at which point personnel from the X-32 and X-35 teams were prohibited from engaging with one another. Only Yates and his Air Force counterpart heading the X-35 program, Lt. Col. Paul Smith, the first government pilot to fly the X-35, were allowed to communicate.

X-32 Integrated Flight Test Team patch., Public Domain

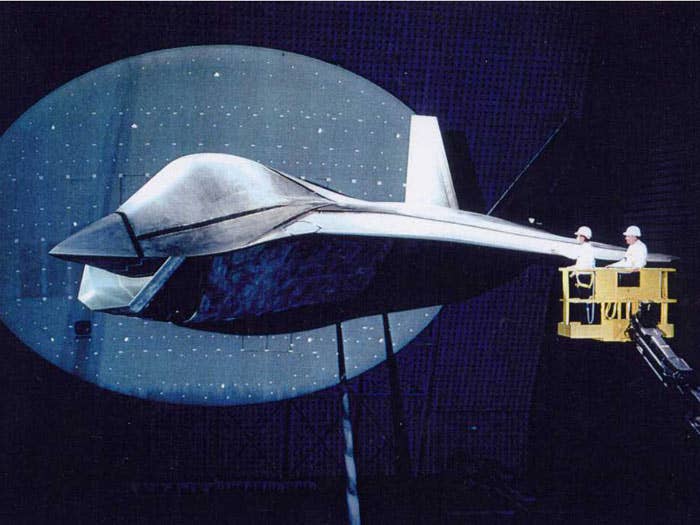

“When I entered the program, they were pretty far along in the design process,” Yates said, adding that the initial X-32 design was a derivative of a secret, stealthy aircraft concept from a “black program” Boeing had in their portfolio and that the company “made the decision to leverage that design for their X-32.” As the interview reveals, that decision may have cost Boeing the lucrative JSF contract.

Boeing X-32 demonstrator., USAF

The initial requirements communicated to both contractors were simple. The competing aircraft would need to be able to take off and land on their own, be capable of carrier landing approaches on a simulated carrier landing area, and be able to execute short/vertical takeoffs and vertical landings. Each core design would need to demonstrate those three capabilities with just two variants.

The testing was very limited due to the limited capabilities of the demonstrator aircraft. There were no extensive requirements for high-G maneuvers or top speeds. “The designs were not meant for those types of evaluation,” Yates said. Instead, each contractor was simply given $1 billion and told they had four to five years to build their JSF design based on the simple requirements.

X-32 and X-35 side-by-side., JSF program office

“This was not a fly-off,” Yates stressed in the interview. “This was each team being given the requirements, and then go fly. Go design, build, and fly your aircraft and then submit a proposal.” The X-32 and X-35 were not put through the same flight testing exercises in a “drag-race” format, but instead developed and conducted separate testing regimes on their own.

Yates said part of the reason for the separate testing schemes was because the program office did not want Congress to summon test pilots to report how each aircraft flew. “They were just demonstrators,” Yates said. “Each contractor would design its own flight test program, what they wanted to show beyond the requirements, and just let the evaluation occur back at the program office with the proposals. The data from the flight tests could clearly be put in those proposals, but it was not about who could fly faster, who could fly better, who could stay up the longest, who could do the most carrier approaches or anything like that.”

Boeing X-32, USAF

Yates was given what he called a “mini-detachment” of 20 maintenance crew personnel and two F/A-18s sent from VX-23 to serve as chase planes during flight tests of the X-32. The Lockheed Martin team, meanwhile, used F-16s stationed at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Yates was most involved with testing how the aircraft responded during carrier approaches and evaluating the handling properties of the X-32.

“Did it feel like an airplane you’d want to take to the boat?” Carroll asked Yates.

“That’s exactly the comment I made,” Yates said in response.

Artist’s conception of a notional U.S. Marine Corps version of the Boeing Joint Strike Fighter based on the X-32., Public Domain

“They had leveraged F-18 handling qualities and control laws extensively for the X-32. Having flown the F-18 at the ship, that was the comment I made after just a couple of FCLP [Field Carrier Landing Practice], what we could call bounce periods, that I would take that aircraft to the ship tomorrow. It was handling that smoothly and precisely. I could make fine corrections, I could make gross corrections back to the centerline, back to the glide path. There were no issues with the handling qualities with the X-32 that I flew.”

Carroll then asked specifically about the STOVL tests conducted with both aircraft. “That was a big deal,” Yates said. “That was probably the one where we kicked the dirt a little bit and said ‘damn.’”

In those tests, the Lockheed Martin X-35 was able to demonstrate STOVL and supersonic flight in the same configuration, while the Boeing X-32 required maintenance crews to make modifications to the aircraft before it could operate in STOVL mode.

A briefing slide outlining different variants of the X-32., Boeing/JSF Program

The X-35’s STOVL design was also “much more technologically advanced,” Yates said. For vertical lift, the X-35 featured a separate 48-inch lift fan fed by an intake behind the cockpit that redirected cool air from above the aircraft to below it. The X-35 also included a swiveling exhaust system that redirected the exhaust from the main engine into the vertical lift system.

X-35B STOVL variant flying above Edwards Air Force Base., USAF

Meanwhile, for Boeing’s X-32 STOVL variant, the company went with a Harrier-like vectored thrust approach using a single engine and exhaust. This variant also included thrust posts and roll posts on each wing for control and stability when in STOVL operation. Unfortunately, that design caused hot air from the X-32’s exhaust to be recirculated into its modified intake, weakening the thrust it could produce and leading to overheating issues.

This gave Lockheed’s design a massive advantage over Boeing’s. “One of the issues that came up was that Boeing’s design was not going to be able to conduct the short-takeoff/vertical landing exercise if you will, the test, at Edwards. They would need to get their STOVL aircraft to Pax River where the air was a little thicker at sea level to create more thrust and have enough safety margin to ensure that aircraft could hover.”

Meanwhile, Lockheed Martin was able to conduct a demonstration in which their STOVL variant executed a vertical takeoff, accelerated to supersonic speeds, and then executed a vertical landing. “That was one place where we said ‘hmm, Lockheed has an advantage from a performance standpoint,’” Yates told Carroll.

Public Domain

It was then that the X-32 test pilot began having a feeling that the JSF program office would be “hard-pressed to lean towards the Boeing design,” for a number of reasons. “Number one, because what they demonstrated was not their proposed final design. Lockheed’s was. And the fact that the Lockheed design had performed better than the Boeing design.”

Yates said there was “great consternation” about the fact that Boeing’s initial design was not the same as what was eventually submitted as their proposal for a production design. By contrast, Yates said, “the Lockheed design was pretty close to what they submitted” for their production proposal. With Boeing’s demonstrator versus its production design “you went from sort of a delta-wing airplane to a more conventional wing version,” Caroll added.

A mockup of what the production ‘F-32’ would have looked like. Gone is the big delta wing, with the aircraft taking on a more traditional fighter-like appearance., Boeing

For a look at what the Boeing X-32 could have looked like in its final production, check out this past feature of ours that includes original artwork from Adam Burch at Hangar-B.com.

An artist’s conception of Boeing’s production design for the F-32., Adam Burch/Hangar-B.com

An artist’s conception of Boeing’s production design for the F-32., Adam Burch/Hangar-B.com

The delta-wing X-32 demonstrator that he flew had no horizontal stabilators (stabilizer-elevator), a control surface that offers more control of an aircraft’s pitch at high speeds. “In the analytical process that Boeing undertook to decide what the final design would be, they actually changed horses mid-stream and said ok, we’re going to go with a more conventional, little bit of a delta-wing, but it also would have a conventional tail, as well.’”

Carroll then brings up what he calls the other “unspoken sense” of why the X-35 won the JSF competition, what he calls the “cosmetic vanity piece.” For two decades now, the X-32 has been the butt of jokes and a frequent entry on “ugliest aircraft” lists.

Yates agrees, replying that “the X-35 looked more like a fighter than the X-32. And while you might say it looked like an A-7, compared to the X-35, the X-32 was not an aesthetically pleasing or typical fighter-looking aircraft. Boeing knew they had a problem with that, if you will, and to address it, they had a little mantra that said ‘look, you’re taking it to war, not to the senior prom.’ That got a lot of traction.”

Joint Strike Fighter Program Office

“In time, we would have grown to like it, right?” Carroll asked. Yates then picks up a model of the X-32 and turns it to the camera so that the aircraft’s distinctive wide-mouthed chin-mounted intake. “That’s the problem,” Yates said as both men laugh. Yates then turns the model so that the intake faces upward and its delta-wing planform can clearly be seen from a top-down perspective. “That is a pretty cool-looking airplane.”

A Boeing X-32, USAF

“Its curb appeal is limited,” Carroll added. “It looks kind of goofy when it’s taxiing.” Carroll said that “many anecdotally said that was the final straw, the aesthetics, the fact that the X-32 was, let’s just say it, ugly.”

X-32B at the Patuxent River Naval Air Museum., Wikimedia Commons/Carl Lindberg

The X-32A awaiting restoration. , USAF

“Form matches function,” Yates replied. “Certainly when you look at an X-35 or an F-35, you can imagine that it can go fast, that it’s going to be maneuverable, things we like in our fighter aircraft. It looks more like a traditional Air Force or Navy fighter. Boeing knew they were up against something there. Maybe they didn’t appreciate it in the early stages when they decided to leverage that design, the stealth design they had invested in. And I think that choice was made because it would allow them to save money. They would not have to do clean sheet design with the X-32.”

X-32A during a test flight., JSF program office

Carroll asked Yates what he thought would have happened if the X-32 had won the JSF competition. “Where would that aircraft have been better than the F-35?” he asked.

Yates replied that he believes Boeing demonstrated a more robust manufacturing capability. While he acknowledges that Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works advanced projects division has a “tremendous capability” for prototyping, the test pilot said they don’t “tout their ability to do mass production.” Ultimately, the X-32’s chief test pilot said he thinks Boeing’s final production design would have met the JSF program’s performance requirements just fine, unlike the flight test demonstrator that relied on borrowed concepts.

A full scale test article for Boeing’s X-32 design undergoes trials in a test chamber., Boeing

In the end, the world never got to actually see a real F-32 in its production configuration. However, its lead test pilot clearly feels that Boeing’s decision to put forward a design that was not truly representative of the expected final product, in addition to the jet’s goofy appearance, prevented the project from reaching its full potential. But had Boeing put forward a more refined design from the beginning, it’s possible that the Joint Strike Fighter competition might have gone differently.